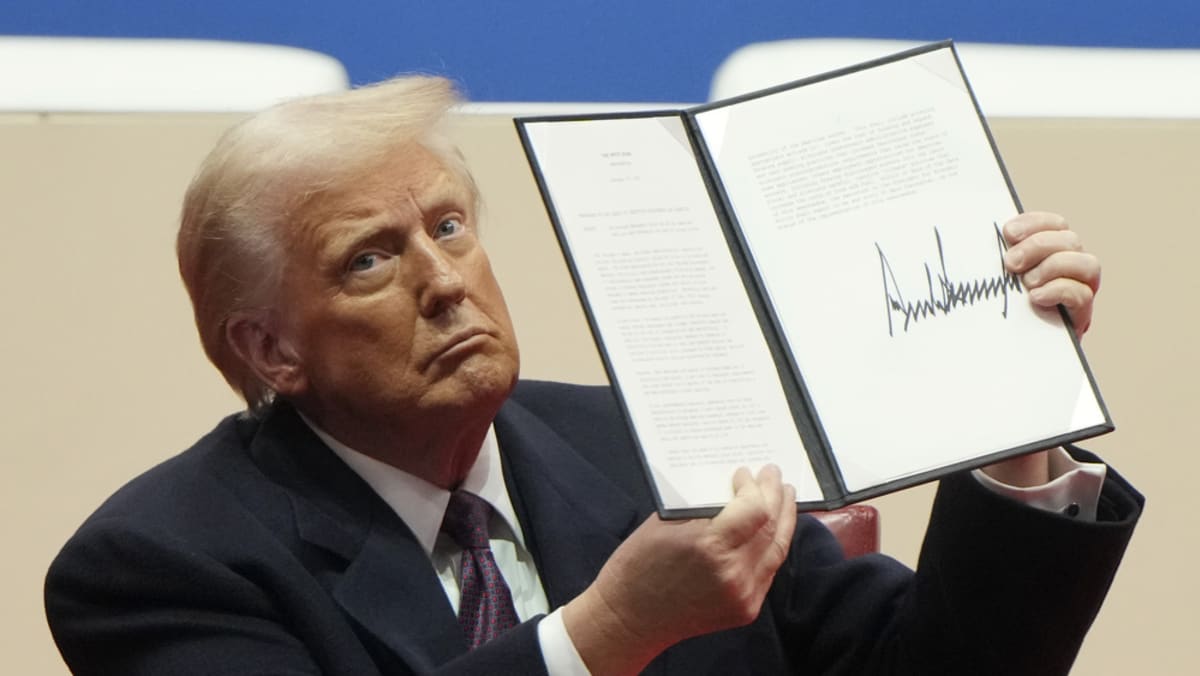

Mr Trump has argued that tariffs can bring manufacturing back to America and balance America’s trillion-dollar trade deficit. Yet he has also floated using tariffs to replace taxes as government revenue and using them as a negotiating tool, sometimes in the same interview.

These goals do not naturally support each other. If he succeeds in reindustrialising America, tariff revenue would fall alongside imports. If he seeks deals, other countries would find creative ways to satisfy him instead of making a potentially risky investment in American manufacturing.

Without a clear explanation of how these goals are prioritised, countries are still left with the challenging task of guessing what Mr Trump wants.

In some cases, a deal may not be possible. White House Trade Advisor Peter Navarro told CNBC that even if Vietnam eliminates tariffs on US products, it would be insufficient due to “non-tariff cheating” measures such as implementing a value-added tax. There is little any country can offer an administration that sees itself as a victim of what others call normal economic practices.

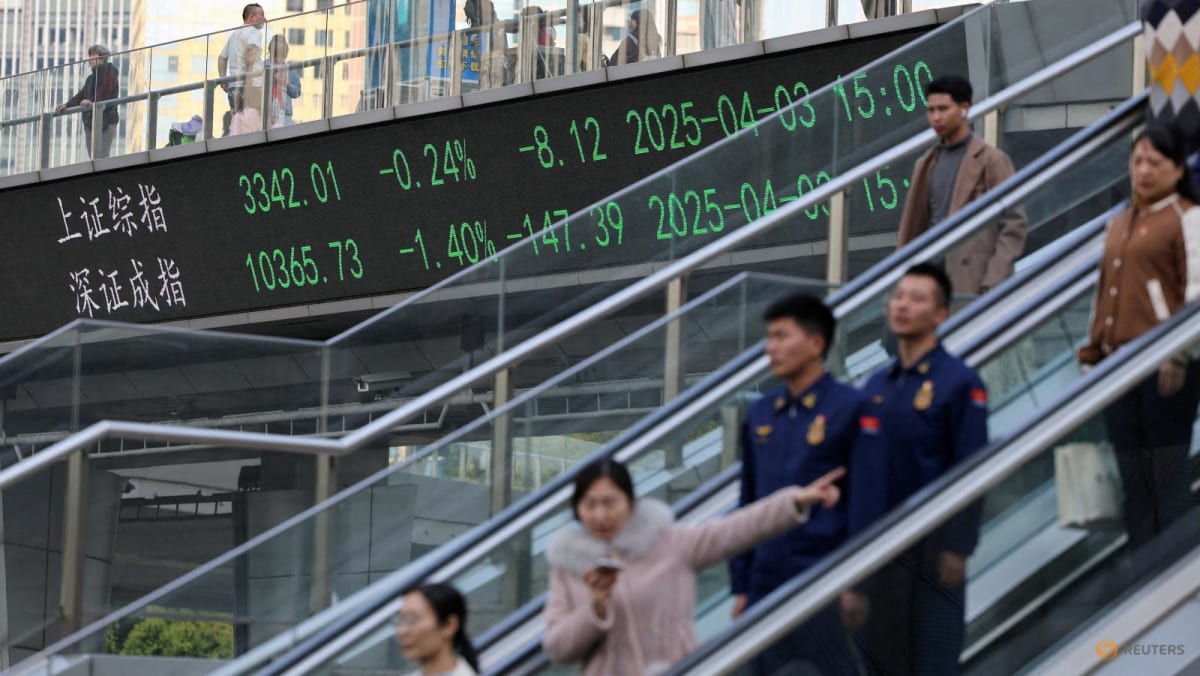

This pervading uncertainty is wreaking havoc with global trade, the very system that was created by America and upon which many Southeast Asian economies depend to fuel their growth. Even if the trade war does not escalate further, the region will still face a bumpy road ahead as supply chains realign and businesses are forced to adapt.