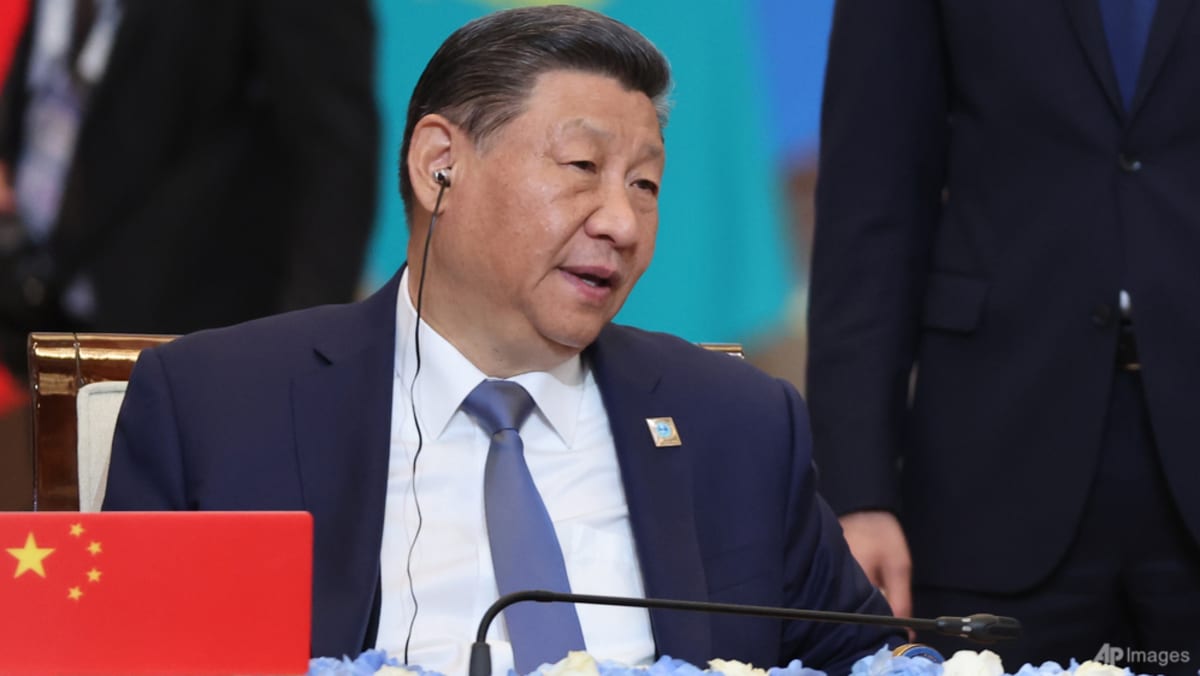

BEIJING: As wars rage on and the global order frays, China is turning to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to project itself as a stabilising force and champion of multilateralism – positioning itself as a counterweight to an increasingly unilateralist United States, say analysts.

The upcoming summit in Tianjin, set for Aug 31 to Sep 1, will be the bloc’s largest to date – a forum bringing together powers at war or often at odds, including Russia, Iran, India, Pakistan and China.

But even as it offers Beijing a high-profile platform to advance its multipolar vision and burnish its global leadership credentials, observers warn that internal divisions could blunt those ambitions, reducing the gathering to optics and rhetoric over substance.

Hosted by China for the first time since 2018, the Tianjin summit is expected to draw more than 20 heads of state and 10 leaders of international organisations.

The guest list includes Russian President Vladimir Putin, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian and United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

This year’s summit will also be notable for the high-level representation from Southeast Asia.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto and Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh are all scheduled to attend in person, alongside leaders from Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

A SUMMIT OF SCALE AND SYMBOLISM

Formed in 2001, the SCO evolved from the “Shanghai Five” – a loose forum created in the mid-1990s by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to resolve border disputes and build trust along their frontiers.

In the two decades since, it has expanded to 10 full members, now including Uzbekistan, India, Pakistan, Iran and its newest entrant, Belarus. The bloc also counts Afghanistan and Mongolia as observers, along with 14 dialogue partners ranging from Türkiye and Sri Lanka to Cambodia and Myanmar.

For Beijing, hosting this year’s summit is about scale and visibility, with analysts saying the message it hopes to project is one of clout, influence and convening power in a turbulent global climate.

“When Russia or India hosted in the past, the summits were relatively modest. This time, China has poured far greater diplomatic resources into the event,” Lin Minwang, vice dean of Fudan University’s Institute of International Studies, told CNA.

He added that the symbolism matters too, pointing out that the SCO is the only international organisation named after a Chinese city – in this case, Shanghai.

“(It is) a distinction that explains why Beijing has consistently attached special importance to the bloc and its chairmanship,” Lin said.