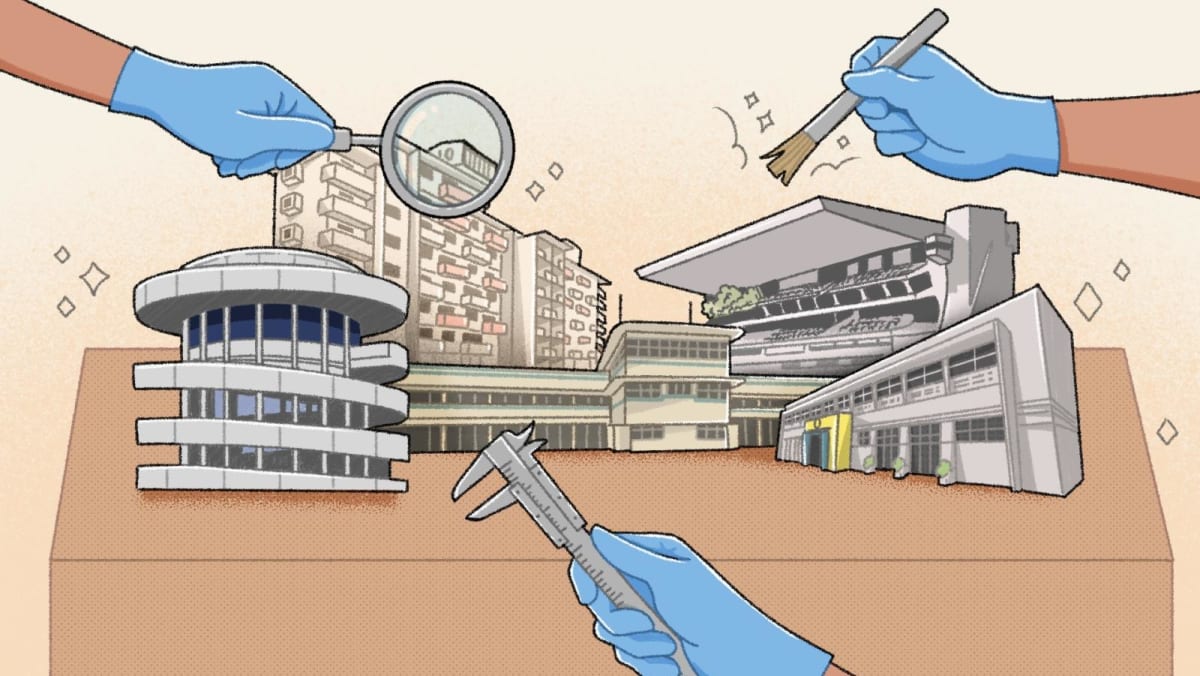

Taken together, the sites provide a tangible and holistic snapshot of Singapore’s development over the years.

Dr Yeo of ICOMOS said the conservation of the five sites adds to a fuller and more nuanced narrative of the era that they were built in.

Their architecture, he noted, also coincided with major global shifts such as World War II and Singapore’s own independence and urban transformation.

For instance, the post-war focus on defence in the 1950s coincided with the expansion of the Royal Malayan Navy and the completion of the former naval base. In the same decade, SIT also worked to address urgent post-war housing needs, as seen in developments like the Dakota Crescent estate.

He then added that there are other sites beyond the five that are worth considering too.

“It is essential to consider other conserved buildings, those yet to be conserved, and even those lost to history. Together, they offer a more comprehensive understanding of Singapore’s architectural and developmental journey.”

CONSERVING SPACES OF EMOTIONAL RESONANCE, EVERYDAY SIGNIFICANCE

The experts also noted that there is a shift towards valuing everyday heritage – beyond just colonial-era monuments – in Singapore’s conservation efforts.

Mr Ho of the Urbanist Singapore said: “We are seeing a broader recognition that heritage includes not just colonial buildings or shophouses, but also post-independence spaces tied to nation-building and community life.”

He added that the five sites reflect a willingness to conserve not just the “monumental or visually striking”, but also spaces with emotional resonance and everyday significance.

“It reflects a growing recognition that places tied to daily life and collective memory deserve as much attention as grand landmarks. That is an encouraging step forward.”

Agreeing, Mr Devadas said that the proposals acknowledge that buildings that once served more functional purposes are also important sites of heritage and memory, alongside the more familiar state and cultural monuments.

NUS’ Dr Joshi highlighted that nearly all of Singapore’s 75 gazetted national monuments are colonial-era structures.

The repurposing of such “less significant” 20th-century buildings could represent a “democratisation of heritage”, he added.

On Jun 25, URA will unveil the Draft Master Plan 2025, a blueprint outlining Singapore’s detailed land use plans for the next 10 to 15 years. The conservation proposals for the five sites will be presented as part of its public exhibition.

Ahead of that, experts told CNA TODAY that some key principles to guide conservation efforts include ensuring that any new use of the site aligns with its original purpose, and that any new design respects the heritage significance of the original structure.

Where possible, original materials and building techniques should also be employed in restoration works.

Equally important, they said, is involving the community early in the process – to ground conservation in shared memory and to ensure it stays accessible.

Mr Ho from the Urbanist Singapore said: “Make (the site) accessible, meaningful, and visible. A conserved building that no one enters is little different from a demolished one.

“Additions or interventions should also be reversible. Future generations should have the freedom to update, not be trapped by our decisions.”

Mr Devadas also highlighted the importance of the site not becoming part of a “private fenced-off development”.

“The sites should become part of the surrounding area’s community life rather than being monuments to gaze upon,” he added.

Agreeing, Mr Ho said: “Preserving only the shell without public access risks turning heritage into a backdrop rather than a lived experience. A meaningful conservation project keeps the building in motion. It remains part of daily life.”

Beyond the physical conservation of the sites, the experts also pointed to the need to preserve the intangible heritage and social memories tied to these places.

Ultimately, the sites carry “emotional memory”, and losing these would mean losing the physical evidence of stories that have shaped the nation, said Mr Ho.

“Conservation is not about freezing time. It is about keeping history visible and usable. Every building we preserve gives Singapore more cultural depth and more space to reflect.”

For the Merdeka and Majulah generations, returning to the sites could bring back memories of who they were, who they were with, and what Singapore was striving to become back then.

For younger Singaporeans, these places offer a tangible glimpse of the country’s early years – which must also be paired with “thoughtful heritage interpretation and storytelling”, said Mr Ho.

“A city without visible layers of accessible history becomes harder to love and harder to explain to the next generation.”