WASHINGTON :The explosion of a star, called a supernova, is an immensely violent event. It usually involves a star more than eight times the mass of our sun that exhausts its nuclear fuel and undergoes a core collapse, triggering a single powerful explosion.

But a rarer kind of supernova involves a different type of star – a stellar ember called a white dwarf – and a double detonation. Researchers have obtained photographic evidence of this type of supernova for the first time, using the European Southern Observatory’s Chile-based Very Large Telescope.

The back-to-back explosions obliterated a white dwarf that had a mass roughly equal to the sun and was located about 160,000 light‑years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Dorado in a galaxy near the Milky Way called the Large Magellanic Cloud. A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion km).

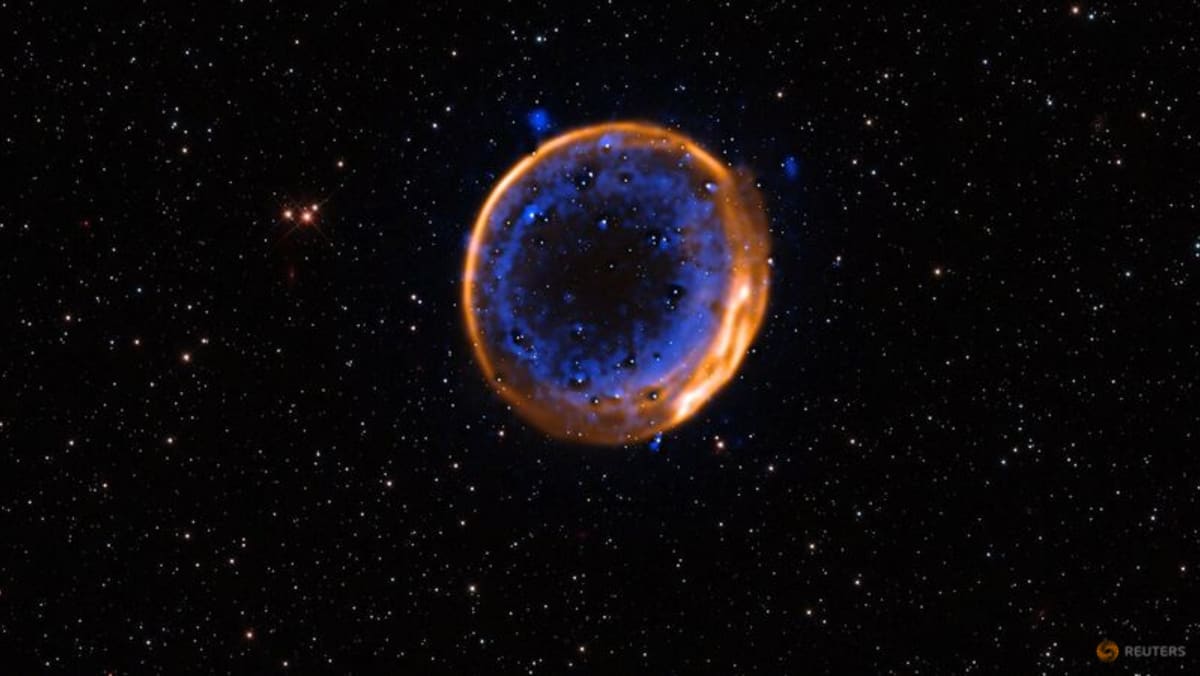

The image shows the scene of the explosion roughly 300 years after it occurred, with two concentric shells of the element calcium moving outward.

This type of explosion, called a Type Ia supernova, would have involved the interaction between a white dwarf and a closely orbiting companion star – either another white dwarf or an unusual star rich in helium – in what is called a binary system.

The primary white dwarf through its gravitational pull would begin to siphon helium from its companion. The helium on the white dwarf’s surface at some point would become so hot and dense that it would detonate, producing a shockwave that would compress and ignite the star’s underlying core and trigger a second detonation.

“Nothing remains. The white dwarf is completely disrupted,” said Priyam Das, a doctoral student in astrophysics at the University of New South Wales Canberra in Australia, lead author of the study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“The time delay between the two detonations is essentially set by the time it takes the helium detonation to travel from one pole of the star all the way around to the other. It’s only about two seconds,” said astrophysicist and study co-author Ivo Seitenzahl, a visiting scientist at the Australian National University in Canberra.

In the more common type of supernova, a remnant of the massive exploded star is left behind in the form of a dense neutron star or a black hole.

The researchers used the Very Large Telescope’s Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer, or MUSE, instrument to map the distribution of different chemical elements in the supernova aftermath. Calcium is seen in blue in the image – an outer ring caused by the first detonation and an inner ring by the second.

These two calcium shells represent “the perfect smoking-gun evidence of the double-detonation mechanism,” Das said.

“We can call this forensic astronomy – my made-up term – since we are studying the dead remains of stars to understand what caused the death,” Das said.

Stars with up to eight times the mass of our sun appear destined to become a white dwarf. They eventually burn up all the hydrogen they use as fuel. Gravity then causes them to collapse and blow off their outer layers in a “red giant” stage, eventually leaving behind a compact core – the white dwarf. The vast majority of these do not explode as supernovas.

While scientists knew of the existence of Type Ia supernovas, there had been no clear visual evidence of such a double detonation until now. Type Ia supernovas are important in terms of celestial chemistry in that they forge heavier elements such as calcium, sulfur and iron.

“This is essential for understanding galactic chemical evolution including the building blocks of planets and life,” Das said.

A shell of sulfur also was seen in the new observations of the supernova aftermath.

Iron is a crucial part of Earth’s planetary composition and, of course, a component of human red blood cells.

In addition to its scientific importance, the image offers aesthetic value.

“It’s beautiful,” Seitenzahl said. “We are seeing the birth process of elements in the death of a star. The Big Bang only made hydrogen and helium and lithium. Here we see how calcium, sulfur or iron are made and dispersed back into the host galaxy, a cosmic cycle of matter.”