LEAVING VIETNAM

The year was 1981.

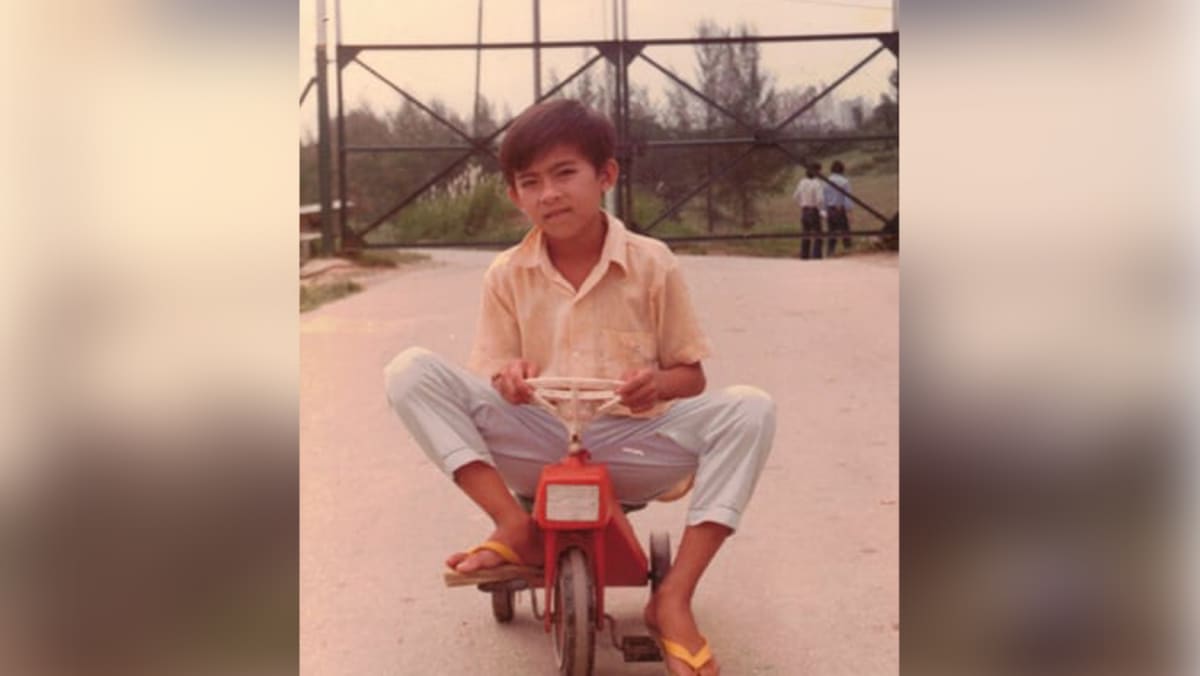

Ten-year-old Thao, the eldest of six children, was living in the south of Vietnam between Ho Chi Minh City and Dalat. His parents worked as farmers to raise him alongside his four younger sisters and younger brother.

The United States had withdrawn the last of its military forces from Vietnam in 1973. The Vietnam War came to an end in April 1975 when Saigon – the capital of South Vietnam – fell to North Vietnamese forces.

In December 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia to topple Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge regime. Soon after, in February 1979, Chinese troops launched a surprise attack on northern Vietnam, sparking the brief but intense Sino-Vietnamese War.

On the back of years of conflict, a family friend approached Mr Dinh’s parents with a request: a loan to help send his son overseas.

In return for the favour, his parents asked that Mr Dinh be taken along too.

“We were very conscious that a lot of young men were being conscripted. Fearing that that would be the future for me, they wanted me to go overseas,” he said.

The plan was to get Mr Dinh out of Vietnam first. His family would follow later, with hopes of reuniting abroad.

“I was sort of like a pathfinder. So after I was picked up and went into the camp, I would send communication to my parents to say that I made it.”

This marked the start of Mr Dinh’s journey to Singapore.

The arrangement was for the two boys to meet in Saigon, where they would be handed over to a group of people who would take charge of the journey from that point on.

“We started out from the city, but the way they planned it was a bit tricky – that instead of meeting up on a boat at the coast, we (wanted to) avoid attention … so we would break up into small, different groups and start out in little boat taxis in the city and then go over to the coast.

“Once at the coast, we jumped onto a bigger taxi and then – I don’t know how many, but dozens or something – medium taxis then transported us out to a bigger boat.

“Apparently the (big) boat was only 12.5 metres in length, and by the time we landed in Singapore, we found out there were 138 people on the boat.”

They set off from Saigon under the cover of night, hoping the boat would make it undetected into international waters, where a passing cargo ship might pick them up.

But about a day into the journey, the engine failed and the boat was left drifting at sea.

“I was very seasick,” Mr Dinh recalled. “Everything was so overwhelming.”

“We drifted, I believe, for four days, then we were picked up at sea around the fifth day by a Dutch oil tanker.”

As they had been drifting at sea, a fierce storm bore down on them.

“We were sort of preparing ourselves (for the worst),” said Mr Dinh.

“We said our prayers and all that … and I think the water was up to the chest in the boat.”

At that point, Mr Dinh said he was knocked out and “dead seasick”. When he finally opened his eyes, he thought he was staring at a “huge city” in front of him.

“It was actually the oil tanker. It was so huge that it appeared to be like a city.”

Yet while it seemed help had arrived, the storm was so strong that they could not steer their boat close enough to the ship.

Instead, crew members aboard the oil tanker threw down a rope. They instructed Mr Dinh and others in the group to secure the rope to their smaller vessel, and to be towed alongside the bigger ship until the storm had eased.

Once the storm had passed, the crew lowered ropes and ladders to bring the passengers safely aboard.

“I was picked up at sea on August 15, 1981, and I believe it took a day or two to get on the ship and into the camp,” said Mr Dinh. “So around mid-August 1981, I came into the camp. I was 10 years old then.”

LIFE AT THE HAWKINS ROAD CAMP

Mr Dinh still remembers his first impression of Singapore after arriving at night and making the journey to the Hawkins Road camp.

“From the city towards the camp, it was dark and I was a bit scared that we were going into a jungle,” he said.

“And then we entered the camp … and I just took things as they were, day by day.”

According to an October 1981 report by The Straits Times, one challenge faced by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) was ensuring that refugees left the Hawkins Road camp within the agreed three-month window. Often, accepting countries were not able to process them that quickly.

Managing the camp’s population cap was also a struggle. In August that year, for instance, an estimated 4,000 refugees were living in the camp waiting to be resettled – far above the 1,000-person limit, the report said.

Mr Dinh, who arrived that August, remembers this clearly.

“When I came into the camp, I think it would have been almost the peak of the refugee crisis. The camp was literally full,” he said.

Travelling alone, he was classified as an unaccompanied minor upon arrival. But the on-site orphanage or “minor house” – meant to house children like him – was “packed full” and could not take him in, he recalled.

“So I slept right next to the gutter outside, near the soccer field at house number 21.”

The camp functioned very much like a village.

Mr Dinh recalled a grocery store and coffee shop within the compound. There was also a library, classrooms where English lessons were held for the refugees, and a hospital that also served as a mental health facility.

“At the early stages, I did enrol into (the classes) to learn English. But then the class would change so quickly – people left so quickly and new people were coming in. (It was) really chaotic and after a while, it just didn’t get anywhere.”

He also remembered being given a daily allowance of S$2.50.

“Each time, I would go and buy an apple at the grocery store in the camp, with a bottle of Coke,” said Mr Dinh, adding that he would then sit at a wooden bridge in the camp that overlooked the soccer field.

Because the refugees were expected to be resettled within three months, most people passed through the camp fairly quickly, including many from the same boat Mr Dinh had arrived on, he said.

“I used to cry a lot, because people were coming and going all the time … and they all ended up going before me. So I can remember, there’s a lot of tears (because) I had to say goodbye to so many of them.”

Mr Dinh held on to the hope of reuniting with his family, who were expected to flee Vietnam after him.

“Almost everyday, we knew people were coming in and we all crowded around the gate and around the fence, looking out and hoping that we would find some of our relatives there,” he said.

“I remember that I used to cry everyday, going out just hoping to find my father.”

He also remembered feasting on donations of cabbages that were brought into the camp. “There was an abundance of them, and I used to pickle them and eat them a lot.”

What Mr Dinh lacked in family interactions, he found in part through the kindness of missionaries and local volunteers who came into the camp during his stay there.

Among those who left a lasting impression were a Franciscan priest he fondly called Father Taylor – “who I named my email address after,” Mr Dinh quipped – and a Redemptorist priest and missionary, Father PJ O’Neill.

He recalled how the priests would enter the camp on weekends to conduct Mass, where he often served as an altar boy.

Later on, Mr Dinh also connected with a Singaporean volunteer, Mr Gabriel Tan, who would come into the camp to spend time with the refugees – sometimes even taking them out.

“I did remember that we were allowed to go outside … and I can remember going to a shopping centre at Marsiling,” said Mr Dinh.

“Then I used to take the kids with me to the bridge overlooking Malaysia near the camp … and we used to go along there collecting shells and things out there.”