Mr Lars Nielsen, managing Director of BMW Group Asia, said this initial resistance to AVs is similar to the hesitation seen in the early days of electric vehicles.

“It’s about educating our customers and gaining their trust in the technology by experiencing it themselves,” he said.

Mr Soh from Volt Auto said: “Public trust doesn’t happen overnight; it’s earned. For any new technology, whether electric or autonomous, the biggest question is, people always ask, ‘Is it safe?’

“Trust starts with familiar things.”

Mr Soh observed that during the early days of electric-vehicle adoption, he focused on explaining how the vehicles worked and how to care for the battery.

This openness helped build trust and allowed people to understand the technology, rather than only reacting when something went wrong.

WHERE DOES SINGAPORE GO FROM HERE?

LTA’s move to call for a pilot deployment of AV minibuses marks a milestone, but Dr Chia said the next challenge is “to take away the safety driver and have it truly tele-operated”.

The ability to safely operate AVs without onboard staff members has been a key objective from the start, but society will also need time to adjust.

Beyond the technical hurdles, public education and familiarisation will be key to ensuring acceptance, Dr Chia added.

Younger commuters may adapt quickly, he reckoned.

“The harder part will definitely be for elders and people with disabilities to operate and interact with self-driving vehicles. That’s an area for more work.”

He noted that self-driving public transport may be harder for people with disabilities to use, because tasks now assisted by drivers, including boarding, would need to be automated, unlike in private vehicles where users are already familiar with the controls.

Mr Chow believes that the next phase of AVs in Singapore is not about “hype” anymore since the technology has already reached a level of maturity and has been deployed in other countries.

In addition to Singapore moving towards having AV buses monitored remotely, he said that commuters can also expect expansion to more bus routes and use cases such as midnight services or night feeder buses.

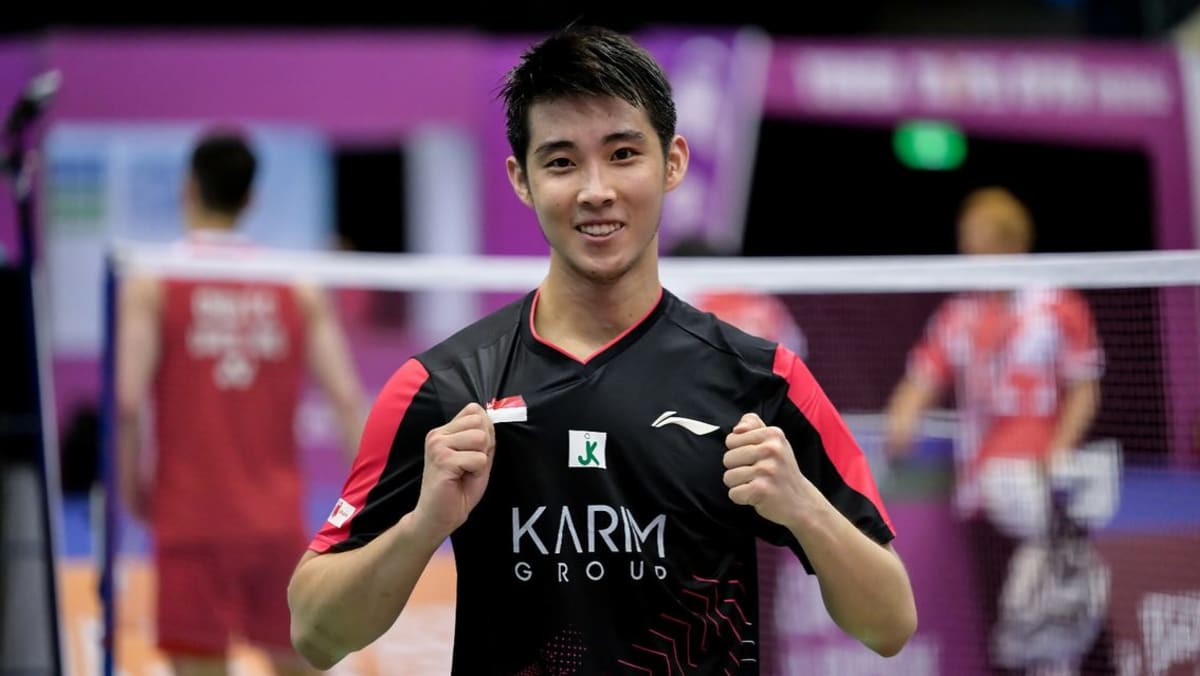

Mr Soh highlighted that beyond safety, a major concern about AVs is job displacement fears among drivers and those reliant on vehicle operation for income.

This is a valid concern, but he noted that in more mature AV markets, such as parts of China, it is a “more nuanced” situation.

For instance, in the city of Wuhan, some AVs are already on the road, but they are not fully independent.

Human operators are integral to the system, he added. They monitor and remotely intervene, allowing one person to manage multiple vehicles, sometimes three or four, from a control centre, creating new job roles.

“You’re no longer just a driver, you become an operator and potentially earn more because you’re supporting more vehicles and doing it in a safer, more controlled environment,” Mr Soh said.

This eliminates long hours on the road, reducing fatigue and high-stress traffic for drivers.

“The real conversation isn’t about replacement, it’s about redefinition … With the right training and support, it can be empowering rather than threatening. It’s about evolving the role, not eliminating it.”