by

Josephine Mulherin

M.A. (Criminology) September 2018

Declaration

I hereby certify that the material which is submitted in this thesis towards the award of the Masters in Criminology is entirely my own work and has not been submitted for any academic assessment other than part-fulfilment of the award named above.

Signature of candidate: Josephine Mulherin

Date: 29th September 2018

Abstract

This research explores the representative nature of jury pools in Ireland and examines how the various stages involved in the jury selection process have the potential to compromise the achievement of a representative jury. Specifically this research addresses how the categories of those who failed to respond to their jury summons, those who were deemed ineligible or disqualified, and those who were excused as of right and for good reason shown, impact the achievement of a representative jury. The headings under which representativeness were examined included age, gender, occupation and nationality. The study was conducted using mixed methodologies and involved a sample of 930 potential jurors who comprised two groups randomly selected for jury duty. Research on the representative nature of jury pools in Ireland is limited, and therefore, jury representativeness was the primary focus of this research.

Findings revealed that the random sample selected in both jury pools examined was representative under the headings of occupation and gender. They were not representative from an age perspective specifically in relation to the under 30 age categories. Findings could not be established with regard to nationality. Of particular importance, in this research, was the high number of potential jurors who, through the various selection procedures, were removed from the pool of potential jurors from which a panel could be selected prior to their appearing in court. This research study revealed that this number comprised over three quarters of the total cohort of potential jurors summoned for jury duty. What was also notable were the number of potential jurors who failed to respond to their jury summons in any way in addition to those who respond but failed to provide complete information despite being asked for it. The findings from this study will inform future policy generation and will create a platform from which future research can be conducted.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people who assisted in the completion of this study.

My work colleagues who carried the workload on the afternoons I attended lectures and most especially to Dolores for her ongoing words of encouragement a huge thank you. To the staff of the court office who facilitated my studies and were extremely helpful at all times it was much appreciated.

To Margaret and Martina who were a constant source of support for my endeavours.

To my good friend, Carmel, for everything – thank you so much.

To my husband Frank who convinced me of my ability to pursue a Master’s Degree and who read and re-read numerous drafts, corrected spelling and grammar and provided much needed constructive criticism, support and encouragement – thank you so much. To my lovely daughter Bláthnaid, for the kind words and the cups of tea – they were most welcome – thank you very much.

And finally, a huge thank you to my supervisor Dr. Mairéad Seymour for her help and feedback throughout the study.

Table of Contents

Declaration

Abstract

Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures

List of Appendices

Table of Case Law

1. Introduction

1.1 Context of the Research

1.2 Rationale

1.3 Aims and Objectives

1.3.1 Aims

1.3.2 Objectives

1.4 Research Questions

1.5 Research Design

1.6 Summary of Chapters

2. Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Critical Analysis of the Juries Act, 1976

2.2.1 Qualification and liability for jury service

2.2.2 Ineligibility

2.2.3 Disqualification

2.2.4 Excusal from jury service by county registrar as of right

2.2.5 Excusal by county registrar for good reason shown

2.2.6 Challenges for and without cause shown

2.3 Impartiality and Citizenship

2.3.1 Impartiality

2.3.2 Citizenship

2.4 Summary

3. Methodology

3.1 Research Approach and Method

3.1.2 Observation Methodology

3.1.3 Statistical Data

3.2 Sampling

3.3 Survey Design and Data Collection

3.4 Data Analysis

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Contributions of the study

3.7 Limitations of the study

4. Presentation of Findings

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Main Findings – Quantitative

4.2.1 Gender

4.2.2 Age

4.2.3 Occupational status

4.2.4 Jurors who accepted summons to perform jury service

4.2.5 Ineligibility and disqualification

4.2.6 Excusal from jury service by county registrar as of right

4.2.7 Excusal from jury service by county registrar for good reason

4.3 Main Findings – Qualitative

4.3.1 Physical description of courtroom

4.3.2 Call-over by court registrar

4.3.3 Waiting time between call over and the judge coming on to the bench

4.3.4 Call-over of cases on court list

4.3.5 Judge addressing potential jurors

4.3.6 Random selection of jurors

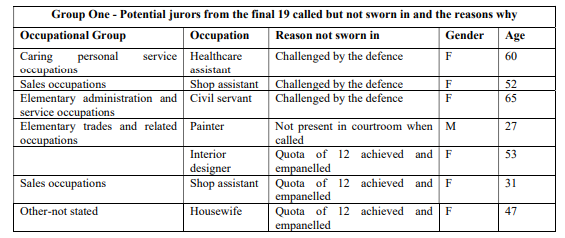

4.3.7 Peremptory challenges

4.3.8 Other points noted during observation

5. Discussion, Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Discussion

5.2.1 Nationality

5.2.2 Age

5.2.3 Ineligibility and disqualification

5.2.4 Excusals by the county registrar as of right

5.2.5 Excusals by the county registrar for good cause shown

5.2.6 Peremptory challenges and excusals granted to potential jurors

5.3 Conclusion

5.4 Recommendations

References

List of Tables and Figures

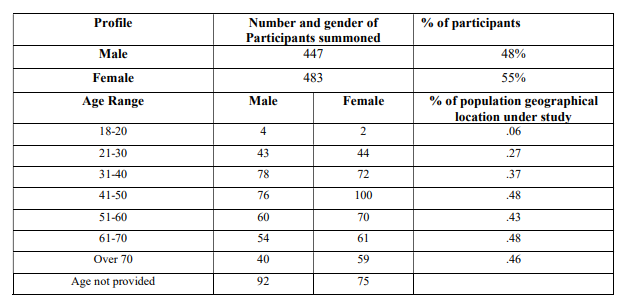

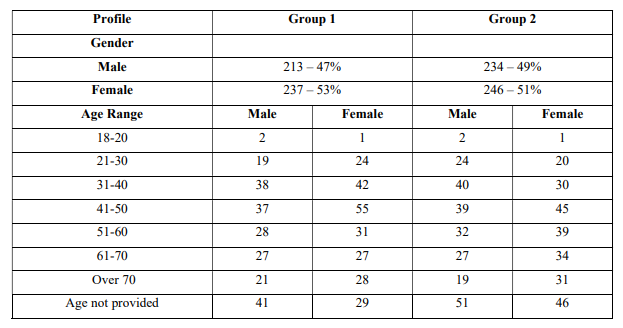

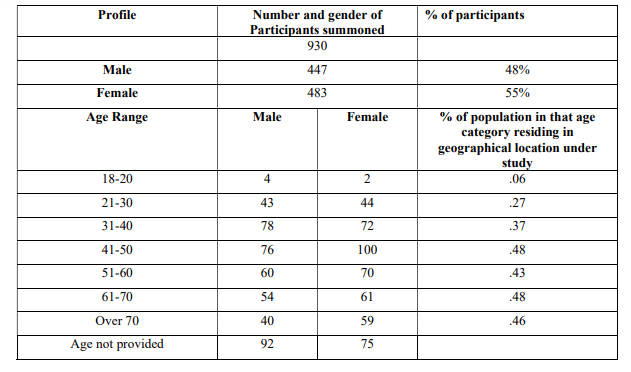

Table 1 Summary profile of the potential jurors summoned for jury service

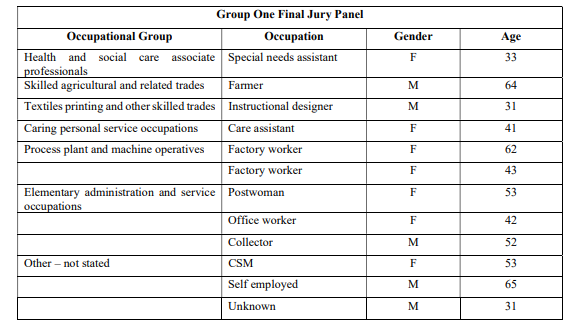

Table 2 Final Jury Panel – Group 1

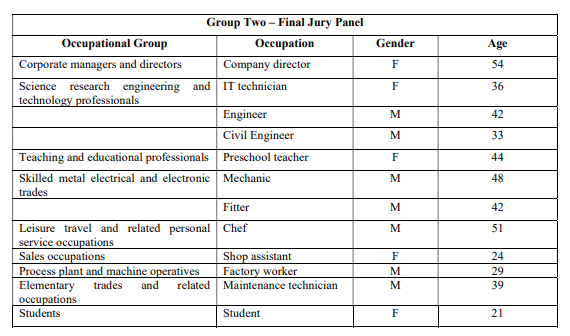

Table 3 Final Jury Panel – Group 2

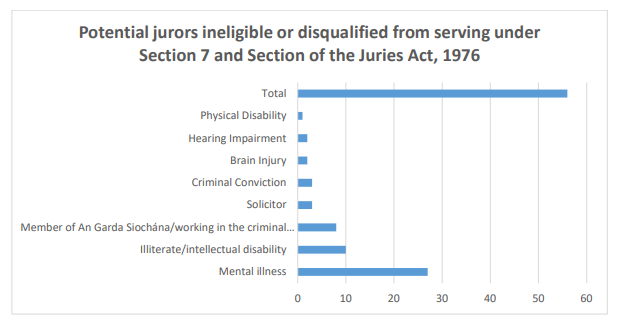

Figure 1 Potential jurors ineligible or disqualified from jury service

Figure 2 Potential jurors who applied to be excused as of right

Figure 3 Potential jurors excused for good reason shown

Figure 4 Pathway through jury selection for Group 1

Figure 5 Pathway through jury selection for Group 2

List of Appendices

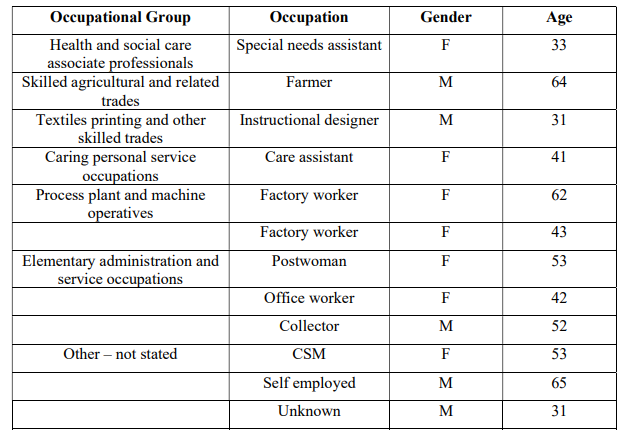

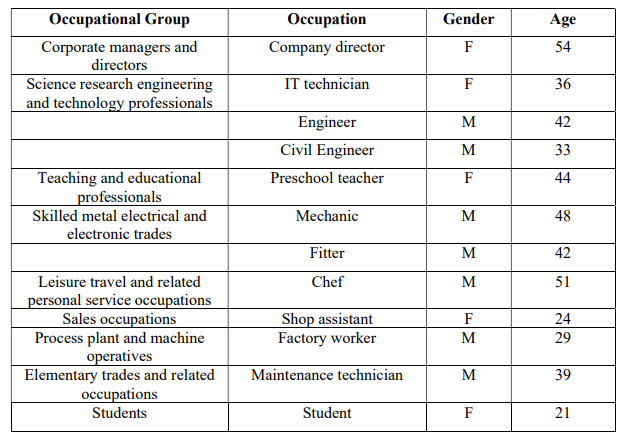

Appendix A – Summary profile of potential jurors

Appendix B – Occupation groups summoned and those who accepted

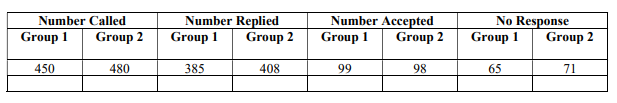

Appendix C – Number of jurors summoned, those who replied, those who accepted and those who gave no response to their jury summons

Appendix D – Observation notes

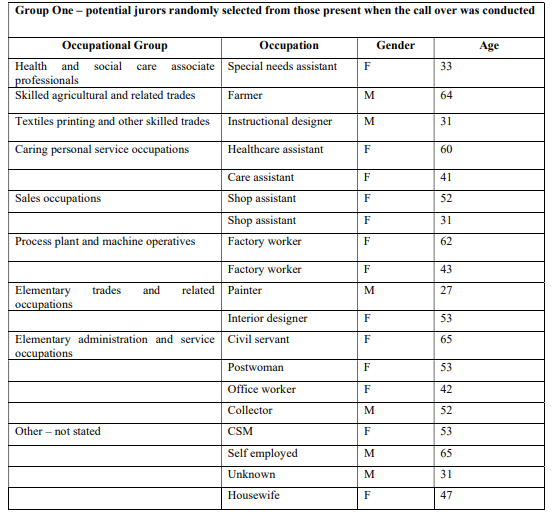

Appendix E – Group 1 – Potential jurors randomly selected from those present when the call over was conducted

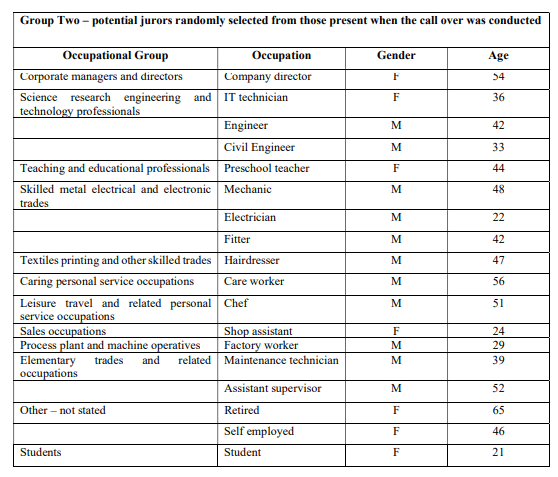

Appendix F – Group 2 – Potential jurors randomly selected from those present when the call over was conducted

Appendix G – Group 1 – Peremptory challenges and final jury panel

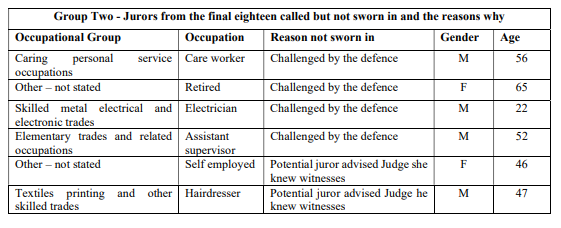

Appendix H – Group 2 – Peremptory challenges and final jury panel

Table of Case Law

1. De Burca and Anderson v Attorney General [1976] IR 38

2 Attorney General –v- Singer [1975] IR 408

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Context of the Research

The right to jury trial in Ireland is provided for under Article 38.5 of the Constitution of Ireland 1937. This mandatory requirement bestows a very important role on the jury as its members have the power to determine an individual’s guilt or innocence in serious crimes based on the evidence presented to them (Ashworth & Redmayne, 2010).

Coupled with the right of an individual to be tried by a jury for serious crimes is their entitlement to a jury who is selected from a jury pool broadly representative of a cross-section of the community (O’Malley, 2009). In Ireland, the Juries Act, 1976 provides for the law relating to juries and their selection. It dictates the procedures to be followed when selecting a jury and deals with issues including qualification and liability for jury service, selection and service of jurors and individuals who are ineligible and excusable from jury service. It also provides for the removal of potential jurors from the final jury panel by both the prosecution and the defence.

In order to qualify for jury service in Ireland an individual must be 18 years or upwards, be registered on the Dáil electoral register for the county or city in question and be an Irish citizen (Juries Act, 1976). The Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956, as amended, provides that every person born in Ireland prior to the 1st January 2005 has an entitlement to Irish citizenship (Law Reform Commission, 2013 – hereafter referred to as the LRC).

While many aspects of the jury have attracted significant levels of attention and research, the representative nature of juries has not been explored in any detail with the result that little is known about the extent to which the pool from which Irish juries are selected are representative of a cross section of the community. In that regard, research in the Irish context has called for jury panels to be reviewed to determine whether the pool from which potential jurors are being selected reflect the community as a whole (LRC, 2013).

This research is an exploratory study of the extent to which the jury pools from which jury panels are chosen reflect a cross section of the community. This will involve an examination of the issues associated with achieving a representative jury in Ireland with a particular focus on Juries Act, 1976 and how the requirements contained within it have the potential to impact the achievement of a representative jury. This will enlighten a discussion on the potential restrictions policy and legislation places on the ability to achieve representativeness in Irish juries.

1.2 Rationale

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Irish juries are composed mainly of young people, the unemployed and the lower social classes, thereby failing to meet the representativeness standard (Jeffers, 2008). The aim of this research is to determine the extent to which such anecdotal evidence has any basis by presenting evidence clearly outlining the composition of a sample of Irish juries and the extent to which they are representative of a cross-section of the community from which they are selected. The findings from this research will not only inform future policy creation but will also provide a platform from which future research can be conducted.

1.3 Aims and Objectives

1.3.1 Aims

To determine the extent to which the jury pools randomly selected for jury service in Ireland are representative of a cross-section of the community and to determine how the subsequent selection processes impact jury representativeness.

1.3.2 Objectives

- To address the knowledge gap regarding the reality of jury representativeness in Ireland.

- To examine the impact each section of the Jury Act, 1976 has on the achievement of a representative jury taking into account those disqualified, those excused as of right or for good reason shown and those who do not reply in any way to their summons.

- To present accurate findings on the impact of all excusals including peremptory challenges on jury representativeness.

- To contribute towards policy generation and legislative change which, it is argued, are necessary to address jury representativeness in Ireland.

1.4 Research Questions

- What is the representative nature of the jury pool randomly selected under the headings of age, gender, occupation and nationality at the outset of jury selection?

- What impact has the category of those ineligible/disqualified on representativeness?

- What impact have excusals as of right and for good reason shown on representativeness?

- How does the failure to respond to a jury summons impact representativeness?

1.5 Research Design

This is both a quantitative and qualitative piece of research conducted through the analysis of raw data and through observation of court proceedings. Non-probability sampling in the form of convenience sampling will be used with the sample being selected from a court office on a date which was dictated by their court calendar. Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel.

1.6 Summary of Chapters

Chapter 2 will present an in depth analysis of the Juries Act, 1976 from the perspective of the potential impact particular sections within it have on the achievement of a representative jury. Attention will then focus on the theoretical perspectives of citizenship and impartiality as they relate to jury service. Empirical research from other jurisdictions regarding the representative nature of juries will be explored. The chapter will conclude with research in the Irish context relating to jury representativeness.

Chapter 3 will focus on the research approach and methods used within the study including information on the mixed methods approach which was selected for this research and justification for having done so. The procedures followed together with ethical considerations and limitations of the study will also be outlined.

Chapter 4 is divided into two sections. The first section will open with detailed information on the quantitative findings of the research followed by the qualitative findings. Findings will be presented using tables, bar charts and figures as appropriate supported by a narrative.

Chapter 5 will comprise an amalgamation of the discussion, conclusions and recommendations as a result of the study. The discussion will be supported by research from the literature review and additional research, where appropriate, which supports the findings from this research.

The Chapter which follows will comprise a review of the literature consulted for this research.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This literature review chapter will begin an in depth examination of the Juries Act, 1976 and how the requirements contained within it have the potential to impact the achievement of a representative jury. This will enlighten a discussion on the potential restrictions policy and legislation places on the ability to achieve representativeness in Irish juries.

Attention will then be directed towards the theoretical perspectives of impartiality and citizenship as they relate to jury service. This will facilitate an exploration and critical analysis of the institution of jury service with specific emphasis being directed towards how they impact representativeness. Empirical evidence from an international perspective will be relied upon to support this discussion and to facilitate a comparative analysis of the difficulties encountered in achieving a representative jury.

The term representativeness, as it relates to jury trial in Ireland;

“encompasses the concepts of random selection and independence …… this means that juries are intended to be composed of a representative cross-section of the community, which is ensured through the process of random selection from a pool of potential jurors, and which thereby promotes the independent nature of the jury, and society’s participation in the institution” (LRC, 2013, p. 12).

Representativeness as it applies to the makeup of jury panels has been acknowledged as a complex issue (Howlin, 2012). A combination of factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, race and occupation has the potential to impact the achievement of a broadly representative jury (Jeffers, 2008). Research argues that representativeness gets to the heart of what the modern jury is for by allowing lay persons to participate in the criminal justice process in a meaningful way (Ashworth & Redmayne, 2010). This, they argue, reduces the possibility of subjective and objective bias by jurors which strengthens the overall fairness of the criminal trial.

2.2 Critical Analysis of the Juries Act, 1976

The Juries Act, 1976 was enacted in response to concerns expressed about the representative nature of juries in Ireland as provided for in the Juries Act, 1927. The 1927 Act restricted eligibility to serve on juries to property owners. It excluded women, even if they met the property-owning requirement, unless they themselves made an application to serve. Indeed, a challenge to the constitutionality of this legislation in the De Burca and Anderson v the Attorney General was the ultimate catalyst for the acceleration of the enactment of the Juries Act, 1976 (O’Malley, 2009).

This case involved two members of the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement who were arrested and charged with obstructing a police officer. Having both pleaded not guilty and electing to have the charges against them tried by a jury, they began proceedings challenging the constitutionality of the Juries Act, 1927 which restricted jury service to certain categories of property owners, which, in effect, excluded women. Prior to their case being heard in the High Court, the Report of the Commission on the Status of Women, 1972 was published which provided that women should be qualified and liable for jury service on the same terms as men. This Report, coupled with recommendations made in 1965 by the Committee on Court Practice and Procedure, culminated in the subsequent enactment of the Juries Act, 1976 which currently outlines the law relating to juries in Ireland today (LRC,2013).

This research aims to show how the requirements contained in the Juries Act, 1976 have the potential to impact representativeness in jury composition when selecting juries. In support of this contention, each section of the Act, which it is argued reduces the pool from which potential jurors can be selected, will be examined separately. Statistics from the Central Statistics Office and other Government websites will be relied upon to support this discussion.

2.2.1 Qualification and liability for jury service

Section 6 the Juries Act, 1976 sets out the conditions under which a person qualifies and is liable for jury service. It directs that;

“every citizen aged eighteen years or upwards and under the age seventy years who is entered in a register of Dail electors in a jury district shall be qualified and liable to serve as a juror for a trial” (Juries Act, 1976, p. 2).

This in effect means that if you are not an Irish citizen you are not entitled to serve as a juror in Ireland (Howlin, 2012). The impact of this requirement from a numerical perspective has been highlighted by the Law Reform Commission who advise that removing the citizenship requirement of itself could have the potential to add an additional 200,000 persons to the jury pool qualified for jury service (LRC, 2013).

Records from the Central Statistics Office suggest this number could be much higher as, in the year 2016, 347,233 non-Irish nationals were recorded as forming part of the labour force in Ireland with a further 41,093 in the category of recent immigrants also employed in Ireland at that time (CSO, 2016). It is suggested that not only would the removal of the citizenship requirement increase the jury pool from which potential jurors could be called from a numerical perspective, but it would also assist in selecting a jury which is broadly representative of a cross-section of the community as opposed to being representative of some particular group (Kettles, 2012).

2.2.2 Ineligibility

Section 7 of the Juries Act, 1976 directs that those listed in Part I of the First Schedule to the Act shall be ineligible for jury service. This list, which is quite extensive, includes those primarily involved in the administration of justice. The schedule begins with the President of Ireland and proceeds to include a myriad of persons who meet the ineligibility criteria including judges, former judges, practicing solicitors and barristers, members of the Garda Síochána and court employees. Persons in charge of a forensic science laboratory and members of the Defence Forces are also included in the list together with members of the Reserve Defence Force. Incapable persons described as having an insufficient capacity to read, deafness or other permanent infirmity or those with a mental illness which require hospitalisation or regular treatment by a medical practitioner also make up the list of ineligible persons.

The potential impact of a sample of these exclusions are revealed when statistical data reflecting those employed in some of these ineligible categories is examined. For example, the Department of Justice and Equality reported a staff compliment of 22,260 during the year 2017 (Annual Report, 2016). Furthermore Defence Forces numbers account for 9,500 (Annual Report, 2016). Solicitors employed in Ireland during the same year amounted to 10,000 with barristers numbering 2,300 (CSO, 2016). The rationale for the exclusion of those working within the justice system appears to reside in the possibility that impartiality may be undermined by the fact that such employees may have knowledge of the case or of those involved in prosecuting or defending the case (The Modern Scottish Jury in Criminal Trials, paragraph 4.2).

Coupled with the reduction in numbers of potential jurors from which to choose is the absence of the potential experience and expertise these professions have to bring to the jury panel and the deliberation process. In that regard, Fukurai (1999) argues that juries which are representative of the community complement the other goals of jury selection such as competence and independence, which promote impartiality by reflecting a greater cross-section of community experience (and prejudice) so that no one view dominates.

In the Irish context, this view is supported by Jeffers (2008) who argues that because virtually all categories of professionals are either ineligible or excusable as of right, the well-educated are unlikely to serve on Irish juries. This, he argues, makes it clear that the current jury system does not create pools representative of Irish society. This view is further supported by Coen (2010) who suggests that as many of the exemptions or excusals from jury duty relate to persons employed in the public service, this represents a poor endorsement of the jury system by the State and consequently results in an unfair burden being placed on the private sector.

2.2.3 Disqualification

Section 8 of the Juries Act, 1976 disqualifies those who have received a prison sentence of five years or more in their lifetime or those who have served a term of three months or more in prison or in an institution in the preceding ten years. It follows, therefore, that a person might be convicted of a serious offence of tax evasion and be punished solely with a fine and thereby remain eligible for jury service. Conversely, a person sentenced to a term of imprisonment greater than three months for a minor theft would remain disqualified for ten years after the expiration of the sentence (O’Malley, 2009). These issues have caused researchers to enquire as to why the emphasis is placed on imprisonment as opposed to conviction? (Shaughnessy, 2010). In that regard, the Victorian Law Reform Committee (1996) in New Zealand suggested that while the representativeness of the jury pool is hindered by the disqualification of individuals with a history of imprisonment, the rationale for doing so is linked with the concept of impartiality. In that regard they argue that past criminal behaviour may indicate that a person may be unwilling or unable to come to the jury bench with an unbiased view to allow them pass judgement in a case. They further argue that confidence in the administration of justice may suffer if a person with a recent and serious criminal record is allowed to serve as a juror.

While there are difficulties associated with estimating the number of potential jurors this could disqualify, an examination of the numbers serving prison sentences last year in Ireland suggests that this could be relatively high given that the daily average of individuals in custody during 2017 amounted to 3,680 (Irish Prison Service, 2017)

2.2.4 Excusal from jury service as of right

Section 9 of the Juries Act, 1976 permits the County Registrar to excuse any person whom they have summoned as a potential juror if they are one of the persons listed in Part II of the First Schedule in the Act. This list is again extensive and includes Members of Parliament, the Comptroller and Auditor General, The Clerk of Dail Eireann and Seanad Eireann, and persons in holy or religious orders. Professionals such as doctors, veterinary surgeons, dentists, nurses, mid-wives and pharmacists also have the potential to be excused provided they can show they are currently practicing in their respective professions. A member of staff of either House of the Oireachtas, Heads of Government Departments and Offices and any civilian employed by the Minister for Defence may also be excused on certificate from the head of their respective Departments confirming the urgency or the public importance of their role which cannot be reasonably performed by another or postponed. Principals or heads of colleges, schools or universities also fit the criteria to be excused, again, if they can show that their role cannot reasonably be performed by another or postponed. The same criteria applies to whole-time students. Those aged sixty-five or upwards are also included in this list.

Again, from a numerical perspective, a sample of those in the teaching profession reveals that 91,571 individuals have the potential to be excused from jury service by the County Registrar if they are in a position to show good reason for such excusal (Department of Education & Skills 2016/2017). In other professions, for example, doctors, who numbered 19,000 in 2017, the option to be excused also applies (CSO). It is argued that the proportion of persons with the potential to fit into the excusals bracket poses a considerable problem to and dramatically undermines the achievement of jury representativeness (Cameron, Potter & Young, 2000).

To counteract this difficulty, researchers have argued that limitations be placed on such excusals. For example Jeffers (2008) suggests that the right to be excused could be limited to certain groups during certain times of the year. Taking the clergy as a case in point, Jeffers (2008) argues that they could remain excusable during important religious festivals such as Christmas and Easter. With regard to students and teachers they could remain excusable during term time but should remain obliged to serve if called to do so during the holiday period. This, Jeffers (2008) contends, would go some way towards enhancing the jury pool from a numerical and representativeness perspective.

It is also argued that groups who fall within a number of skilled occupational groups who can claim excusal as of right, deprive the jury pool of a significant stratum of educated members (Chesterman, 2000). Indeed Byrne (2009) contends that by such individuals availing of the right to be excluded, they deny the jury system their specialised knowledge and experience which has the potential to compromise the random selection requirement. In support of such views, recommendations have been made to repeal the existing excusal as of right from jury service and replace it with the right to excusal for good cause shown (LRC, 2013).

2.2.5 Excusals by county registrar for good reason shown

Section 9(2) enables the county registrar to excuse any person summoned for jury service if they can satisfy him/her that there is good reason why they should be excused. Jonakait (2003) suggests that often as many as half the jury panel have the potential to be excused because they claim some pressing or business reason that conflicts with their ability to serve. Noting that such excuses are accepted uncritically as neither the defence nor the prosecution desire to have an unwilling juror confined to the jury box for many weeks, Jonakait (2003) argues that people who are qualified to serve should not be able to compromise the representative nature of juries by seeking to avoid jury service other than on acceptable grounds.

Fukurai (1999) highlights the link between an individual’s socio-economic background and their ability to serve on a jury. Attention is drawn to the potential juror’s ability to make the necessary financial sacrifice to take time off work to attend jury service. In Ireland, lunch and hotel accommodation expenses (where necessary) are met, however there is no compensation to meet the ancillary expenses incurred by jurors. Any out of pocket expenses have to be incurred by the juror themselves rendering it impossible for many people on limited income to participate in the jury system (Shaughnessy, 2010).

This contrasts with the jury system in England and Wales which provides for the payment of travel expenses and subsistence (Juries Act, 1974). Jurors in these jurisdictions are also allowed to claim for any financial loss suffered as a direct result of jury service for example, loss of earnings or benefits, fees paid to carers or child minders, or any other payments made solely as a result of jury service. In that regard, recommendations have been made for a modest daily flat rate payment for jurors in Ireland to enable them discharge travel and subsistence costs. (LRC, 2013). However, at the time of writing, this recommendation has not been implemented.

2.2.6 Challenges for and without cause shown

Section 20 and 21 of the Juries Act, 1976 provides for challenges for cause shown and for challenges without cause shown, often referred to as peremptory challenges in civil and criminal cases. In relation to challenges without cause shown this means that in every criminal trial involving a jury, each accused person and the prosecution may challenge up to seven jurors each without having to provide a reason to the court why they are challenging these jurors. These challenges do not involve any questioning of the juror, hence their peremptory nature. Any challenge without cause shown is generally made immediately prior to a juror taking the oath. If a juror is challenged, they are not included in the jury panel and are excused by the Judge.

In respect of challenges with cause shown, the prosecution and defence teams can object to any number of jurors each but a reason must be given to the Court as to why the objection is being made at the time of the challenge. Whenever a juror is challenged for cause shown and this challenge is allowed by the judge, the juror shall not be included in the jury (Juries Act, 1976).

Peremptory challenges have been criticised extensively throughout several common law jurisdictions predominantly due to their capacity to discriminate against minority groups particularly in multiracial and multicultural societies (Fukurai, 1999) While there is little research in Ireland as to the reasons why jurors are challenged, Jeffers (2008) argues that there is ample anecdotal evidence that peremptory challenges are used to achieve a certain gender, age or racial profile in some cases. It is argued that such challenges suggest “a subjective assessment of the likely attitude of the juror to the challenger’s case, based on matters such as age, sex, appearance, address or employment” (Walsh, 2002, p.835).

The right of peremptory challenge was abolished entirely in England and Wales in 1988 followed by Scotland in 1995. Under Section 13 of the Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act, 2007 the entitlement to peremptory challenges was also abolished in order to prevent the appearance of biased selection procedures (Thomas, 2010).

In the United States all jurisdictions have some system of peremptory challenges in place which facilitates the questioning by counsel for both sides prior to the jury being empanelled (Vidmar, 2000). Research suggests that the main purpose of peremptory challenges is to rid the jury of the types of jurors the prosecution and defence teams find most threatening, and that these types tend to correlate with age, gender, and particularly, race (Myres-Morrison, 2014). It is argued that the use of peremptory challenges raises concerns about the fairness of trials in the state of Florida where evidence suggested that juries formed from all-white jury pools convicted black defendants more often than white defendants. This gap in conviction rates was entirely eliminated when the jury pool included at least one black member (Anwar, Bayer & Hjalmarsson, 2012). While the representative and impartial jury ideal holds no place for peremptory challenges on either side, their use by both sides tends to result in a more homogenous group than that of the population at large and therefore goes against achieving the representativeness of that population (Bennett, 2010).

In that regard Thomas (2010) highlights the desirability of the jury to express the conscience of the entire community and not just the conscience of those least obnoxious to the prosecution and the defence. The process of jury selection should not be a tactical manoeuvre by which each side tries to secure the twelve most sympathetic jurors from their particular point of view as this may cause important classes of the population to be either excluded or disproportionately represented (Thomas, 2010). However, despite the extensive criticism directed towards the use of peremptory challenges throughout several common law jurisdictions, no recommendation has been made to amend the legislation surrounding their use in Ireland (LRC, 2013).

2.3 Impartiality and Citizenship

2.3.1 Impartiality

The Law Reform Commission (2013, p.14) draw on the definition of impartiality proposed by the American sociologist Robert Blauner as follows:

“…. impartiality and independence involves judgement by persons who have no direct involvement in the trial or who, from an objective standpoint of the reasonable observer, would not be regarded as partial or biased …. the concept of impartiality also assumes judgement by persons of independence, with opinions and beliefs and other experience of the realities of living in today’s society”.

While, historically, jurors were selected on the basis of their local knowledge of the facts or from the locality where the case was centred, modern jurors are chosen randomly and on the basis of their complete lack of knowledge of the case or of the parties involved in it (Kettles, 2012). During the empanelling process in Ireland, potential jurors are obliged to bring to the attention of the Court their prior knowledge of any party involved in the proceedings as this invariably causes them to be excused as a juror from that particular case (Juries Act, 1976).

In relation to the achievement of an impartial jury, some research appears to suggest that the concepts of impartiality and representativeness can often come into direct conflict with one another. In that regard Jeffers (2008) contends that a representative jury may not be impartial while an impartial jury may be far from representative. He argues that the perspective from which the right to trial by jury is viewed can determine the importance attached to impartiality. Therefore, if the jury is viewed from the perspective of it being a democratic institution, then greater importance must be attributed to its representative character. However, if it is to be viewed from the perspective of the right of the accused then impartiality must prevail (Jeffers, 2008).

The Law Reform Commission (2013) argue that jury impartiality and jury representativeness are distinct concepts suggesting that jury partiality can be divided into the categories of interest prejudice (which suggests having a pecuniary or personal interest in the outcome of a case) or specific prejudice (having attitudes about specific issues which prevent the juror from reaching an verdict with an impartial mind). Citing tests of reasonable apprehension of bias, attention is directed towards the view of the European Court of Human Rights who hold that the personal impartiality of jurors must be presumed until there is proof to the contrary (LRC,2013).

From an international perspective, Kettles (2012) draws our attention to the central considerations which govern the jury selection process in Canada. He argues that the impartiality of the jury is assured by virtue of its representativeness in that prejudice is randomly distributed and a multiplicity of viewpoints have the effect of either overcoming or drowning out the bias or prejudice of an individual. However, he cautions that courts frequently promote competence or impartiality at the expense of representativeness. In support of this argument he contends that the use of police and other databases to access significant personal information about jurors is inappropriate given the fact that it is inevitable that vetting practices create bias by firstly reducing the representativeness of juries and secondly reducing the confidence the public have in the administration of justice (Kettles, 2012).

The process of acquiring personal information on potential jurors informs the challenging process when the jury is being empanelled. During this process, the prosecution and defence teams can object to a certain number of potential jurors based on the information they have about their personal circumstances. The defendant on trial and the details of the case being tried will also have an impact on the ‘type’ of juror the prosecution and defence teams are hoping will be placed on the jury panel. Noting research from the United States which suggests that an unrepresentative jury can never be viewed as fully impartial Jeffers (2008) highlights the view that jurors can be seen to be bringing the preconceived beliefs of their gender or race to the deliberation process rather than deliberating on the evidence presented.

From an Irish perspective, O’Malley (2003) argues that the impartiality of a jury may be questioned on several grounds. These include the pre-trial publicity a case has attracted which has the potential to introduce bias into jury decision making or indeed matters coming to light during the trial, for example the behaviour of a juror, which may cause the jury to be discharged. To emphasise this point O’Malley (2003) draws attention to People (Attorney General) v. Singer where it transpired that the foreman of the jury was one of the victims in a fraudulent scheme for which Mr. Singer was on trial. Jeffers (2008, p. 2) argues that the requirement for impartiality seems;

“fundamental in the modern criminal justice system” as it would seem to be a key component of the right to a fair trial, which he contends, is now viewed as “an elementary feature of most western legal systems”.

In Ireland, the difficulties associated with the achievement of an impartial jury were more recently evident in the trial of DPP –v- Sean Fitzpatrick where the presiding Judge gave the final jury panel selected for the trial a final opportunity to reflect on whether they were certain of their ability to approach the trial with impartiality. In this case the presiding Judge advised the jury that they must be absolutely impartial to all the parties involved in the case and to return a verdict only in accordance with the evidence presented to them in Court. It was notable, in this instance, that a specially enlarged jury panel of fifteen members (as opposed to the normal twelve) had been sworn in at the Dublin Circuit Criminal Court for the trial with over seventy potential jurors being excused for various reasons prior to the final panel of jurors being sworn in (Ferguson, 2016).

2.3.2 Citizenship

The term ‘citizenship’ can denote many different meanings. Various historical definitions of the term are dealt with succinctly by Howlin (2012, p.156) who notes that “socio-political definitions emphasise citizenship as a status denoting membership of a society”. In that regard she explains that citizenship has to be understood in the context of the power relationships which exist in that society and the political, economic and cultural factors which affect it. Philosophical definitions, she continues, are concerned with questions surrounding the model of citizenship that can best deliver a just society, the role of the state in providing for its citizens’ needs and what the state can expect from the individual in terms of duties. Finally, Howlin (2012) advises that legal definitions of citizenship tend to equate to nationality and to define the rights and duties of citizens in relation to the nation-state.

The citizenship requirement to qualify for jury service in Ireland has been questioned by many researchers who argue that such limitations many impact the representativeness of the jury panel. These include O’Malley (2003) who contends that the citizenship requirement is questionable given the number of non-citizens becoming long-term residents in Ireland. He also references the requirement that potential jurors be drawn from the Dáil electoral register for the relevant jury district. This, he argues, would be acceptable if it was the case that most of the adults living in a particular locality were registered as electors in that locality. However, the need for many young people to work in an alternative location to where they are actually registered to vote calls this into question. Jeffers (2008) argues that virtually all juries are likely to be racially and ethnically homogenous as qualification for jury service is limited to Irish citizens who are Dáil electors. In that regard he notes that as the number of non-citizens living in Ireland is on the increase, this can only result in Irish juries becoming increasingly unrepresentative of Irish society.

In support of this view Shaughnessy (2010) also highlights the demographic transformation in Ireland today and suggests that if the jury pool is to be truly representative of the community the extension of jury service to non-citizen permanent residents or to European citizens resident in Ireland may offer an appropriate solution to this problem. As the jury pool in Ireland represents approximately half of the total population it is questionable as to how jury composition can possibly reflect demographic realities. This view is held by Howlin (2012) who contends that as little thought has been given to the validity of the exclusion of non-Irish citizens from Irish juries that a rationale to justify their continued exclusion is warranted.

The multicultural nature of Irish society today has been acknowledged and various recommendations have been proposed to broaden the jury pool (LRC, 2013). These include the adoption of a similar practice to the United Kingdom where individuals are qualified for jury duty if they satisfy the residential qualification of at least five years since the age of thirteen years. The residency requirement is even lower in New Zealand where, under the Electoral Act, 1993, individuals are entitled to perform jury service if they are over the age of eighteen and have lived continuously in New Zealand for one year. However, while many proposals to extend the jury pool have been recommended, these have not, as yet, been incorporated into the selection of juries in Ireland.

2.4 Summary

The above discussion on the representative nature of the jury pool in Ireland has provided a platform from which the current study can be placed in terms of research, theoretical discussion and policy context. The questions posed relating to representativeness in this research study become more relevant and pertinent in the light of the information which has been revealed in the above literature review. The question of jury representativeness, it is argued, has a practical significance in addition to its implications for future policy and legislative change within the criminal justice system.

Chapter 3 Methodology

3.1 Research Approach and Method

The purpose of this research project was to examine the issues associated with achieving a representative jury in Ireland. In that regard, specific emphasis was directed towards the Juries Act, 1976 which governs the selection of juries and how the requirements contained in this Act have the potential to impact the achievement of a representative jury. Attention was also directed towards the objectivity and subjectivity associated with jury selection and the potential impact such practices may have on the representative nature of the final jury panel. As such the approach to data collection and the epistemological reasoning behind the study needed to take cognisance of a variety of philosophical approaches.

As the intention was to collect statistical information in addition to conducting observational research, the pragmatist approach was chosen. The pragmatist approach allows the researcher to take into account a variety of data collection methodologies whilst simultaneously allowing for an analysis of the information which can be interpreted from a number of different perspectives (Cherryholmes, 1992). A pragmatist perspective also facilitates the application of a mixed methodology approach which includes both quantitative and qualitative data collection processes (Creswell, 2003). The mixed methods approach also gives the researcher the freedom to use different philosophical systems in which to interpret the data, allows for the “what and how” which balances issues of objectivity and subjectivity and permits the mixing of these methodological practices” (Creswell, 2003, p.12). Due to the fact that there were elements of objectivity and subjectivity within the research study, it was important to organise the data collection in a way that was efficient and accessible.

As the standard practice in court offices is to summons potential jurors six weeks in advance of the court date on which they are due to appear, the qualitative aspect of the study was conducted in the first instance followed by the quantitative approach. This decision was informed by the dates on which the Circuit Court was due to sit, (which is dictated by legislation) and by the fact that the raw data available on the Court file relating to the potential jurors summoned for jury service would not be impacted in any way due to the passage of time.

3.1.2 Observation methodology

The use of observation methodology as part of the data collection process relies on an ethnographic approach which takes cognisance of human interaction. It is a challenging approach as the nuances of non-verbal human communication have high levels of differing interpretation and the author needed to be aware of these in order to make sense of the interactions being observed (Morgan, Pullon, Macdonald, McKinlay & Gray, 2016). The observational information then needed to be interpreted in a way that allowed for the relevant extraction of data that could appropriately inform the research question. Event sampling was used to note behaviours of potential jurors prior, during and directly after the court proceedings. The impact random selection of potential jurors had on the representative nature of the final jury empanelled and the role peremptory challenges had to play on representativeness was also noted. The style of the observation methodology was naturalistic/non participatory as by its very nature jury selection cannot be affected by outside forces. This meant that the research environment could not be controlled or manipulated and this was important in the context of understanding the core question within the study.

By observing the flow of the interactions within the jury selection process, the author was enabled to identify and interpret the information as it “unfolded, cascaded, rolled and emerged” (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 86). Although this observational methodological approach was guided by a question – how do the interactions being observed affect the outcome of jury representativeness – the method of recording necessitated a raw data process that required interpretation at a later stage. A two stage process informed the observational methodology. The first included an initial process of observation of potential jurors being introduced to the selection process and the ways in which random selection of potential jurors by the court registrar had the potential to impact jury representativeness. The follow-up observational process took cognisance of the intentional removal of potential jurors by both the prosecution and defence teams through the use of peremptory challenges. It also focussed on the reasons presented to the judge by potential jurors themselves to be excused from having to serve on the jury at the penultimate stage of the final jury being empanelled.

3.1.3 Statistical data

In order to support this data gathering process and to contextualise the more global aspects of jury representation the author engaged in a statistical analysis of the actual numbers that make up the pool of potential jury participants at the beginning of the selection process and how each subsequent stage of selection impacted the representative nature of the final jury panel. With this in mind a quantitative analysis was undertaken to compare and contrast the potential and the actual jury representations. This informed the observations made within the context of the research question. By breaking down the characteristics of the population in the region and gaining an understanding of the socio-economic structures of the said population the author could make some assumptions on the validity of the jury process in the context of its representativeness. The observational methodology added another context which, when combined with the statistical analysis, allowed for a cogent exploration of the underlying principles of the question being asked.

3.2 Sampling

Purposeful non-probability availability sampling was used and data available in the court office selected for study was relied upon. The use of this method of sampling results in not all members of the population having an equal chance of participating in the study. Availability sampling involves the selection of participants as they are readily available and accessible to the researcher (Burton, 2000).

In relation to the quantitative aspect of the study the author was given access to the court office where information relating to the potential jurors summoned for jury service was stored in manual files. These files contained rich data relating to potential jurors’ demographics and, more importantly, contained information relating to individuals who were ineligible, excused as of right, did not reply to their summons or those who were excused by the county registrar for good cause shown. The author was also permitted to gain access to the courtroom on four separate occasions to observe the process involved in juries being empanelled as it happened.

3.3 Survey Design and Data Collection

In order to capture the optimum amount of data to inform the research question, the decision was taken to use a mixed methods approach – observational and statistical data collection. In relation to the observational data collection aspect of the study, the author attended court by appointment on a date a jury was due to be empanelled to get a feel for the process and to establish if the observation method of data collection had the potential to reveal the required information to compliment the statistical data relating to potential jurors.

The initial visit was organised for the end of April 2018 and after this visit it was agreed that the author would attend on three further dates on which potential juries were summoned to appear for jury duty to observe and take notes on the process involved in a jury being empanelled as it happened live in the courtroom. The author attended on the three further dates as agreed. However, it transpired that just one jury had been empanelled during those three visits and therefore one further date had to be arranged with the court office in order to gather what was considered to be a reasonable sample of data for analysis. Observational data collection was conducted on three dates in May 2018 and one during June 2018. During these four visits to observe proceedings, two juries were empanelled.

The normal practice in the court office under study is to summons potential jurors to appear in court at 9:45 a.m. on each day a jury is to be empanelled so that a call over of attendees can be conducted by the court registrar prior to the judge coming on to the bench at 10:30 a.m. On each date of observation the author was in attendance at 9:50 a.m. to secure a seat in a location conducive to achieving the maximum view of proceedings as they played out. During the period prior to 10:30 am, notes were taken on the layout of the courtroom itself and what was contained within it. These details were noted as courtrooms and their surroundings were most likely new to the majority of potential jurors in attendance as indeed they may be to the reader of this research.

Notes were then taken on all proceedings observed as they occurred in real time. Some comments made by potential jurors relating to what they were observing and how they were feeling about the process as it played out which were audible to the author were also noted as it was believed such comments would enhance a discussion on possible apathy or openness towards performing jury service. In total, observation notes were taken on proceedings over four days encompassing a total of 6 hours forty-four minutes observation time.

In relation to statistical data collection, the author attended the court office by appointment on the 20th July 2018 and was given an explanation on how the computer programme selects a list of potential jurors to be called for jury service. It became apparent at this stage that the computer system could only be used on a ‘read only’ basis and that any statistical information would have to be transcribed onto an excel spreadsheet for analysis at a later stage. In that regard, the manual files which contained completed jury summonses relating to the potential jurors being reported on in this study were made available to the author. One file contained details of the first 450 potential jurors summoned for jury service and the other contained details on the second group of 480 potential jurors summoned.

The reason for two files instead of four is that when the court office summonses potential jurors for jury service, they call what they consider to be an adequate number of individuals from which more than one jury panel can be formed. Therefore, potential jurors called for jury duty attend on the first day and depending on whether or not a jury is empanelled on that date, they are asked to return the following week for a second time. After having attended on two dates as requested, potential jurors, whether sworn in to the final panel or not, are excused from jury service for a period of three years. This period of three years can be increased by the Judge in cases where a juror has performed jury service but the evidence heard is of such explicit or serious content that the juror can be excused for longer periods or in some cases, for life.

Therefore, information on 930 potential jurors required transcribing from each jury summons to an excel spreadsheet in order that the data could be analysed. The information available from the summonses included the name, address, date of birth and occupation of jurors who completed and returned their summonses to the court office. There were 143 potential jurors for which there was no corresponding completed or returned summons on the files. Due to the anonymous nature of the research, names and addresses were not recorded by the author. Instead, as each juror had an individual number assigned to them by the court office, information where available was recorded by juror number, gender, date of birth and occupation. The jury summonses also included valuable information on those ineligible for jury service or those excused from jury service and the reasons why. This information was also recorded for analysis.

3.4 Data Analysis

Research contends that a combination of factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, race and occupation have the potential to impact the achievement of a broadly representative jury and therefore, it was on the basis of information available under these headings that the collected data was recorded and categorised for the purposes of later analysis (Jeffers, 2008). While categorisation was relatively straight forward for age and gender – ethnicity, race and occupation proved more difficult. As information regarding ethnicity or race of potential jurors was not requested to be completed on the jury summons, this information could not analysed.

In relation to occupation the variety of roles reported by potential jurors warranted categorisation to facilitate analysis. On that basis it was decided to utilise the categories of employment used by the Central Statistics Office who display their census data on employment records using twenty-seven occupational groups (CSO, 2016). As there was no obvious category under which to place students (who featured amongst potential jurors summoned for jury service) it was decided to add an additional category named ‘student’ to include this group. Data analysis was conducted using Excel spreadsheets. In addition to facilitating the recording of the many variables in the dataset under study, the Excel spreadsheet programme allowed the user to generate statistical results and assisted in the presentation of these results using tables, graphs and charts.

The qualitative data collected for this research required an alternative type of analysis and in that regard thematic analysis was used to reflect common themes in the research findings. As the focus was on the potential impact the Juries Act, 1976 may have on the achievement of a representative jury, attention was directed towards the role of the court clerk, the judge, the prosecution and defence teams and the jurors themselves. Recurring themes were also noted from the pre and post court conversations amongst potential jurors on the court process involved in jury selection. The results are reflected in the research as deemed appropriate.

3.5 Ethical Considerations

The British Society of Criminology Ethical Code outlines the standards to be maintained when conducting criminological research (Code of Ethics, 2006). Consideration was given to these requirements in this research. Informed consent was sought and approved in respect of all parties observed with the exception of the potential jurors themselves. As the study was anonymous in its location and the actions of the jurors were not deemed to impact on the selection process it was determined that the anonymity of potential jurors would be safe guarded in the study. Cognisance was also afforded to the ethical considerations dictating data security and storage and in that regard the laptop used was password encrypted. Raw data was stored in a court office at all times.

The dataset was anonymised and therefore were not subject to data protection requirements (Healy, 2009). While Thomas (2010) highlights the requirement to ensure secrecy when conducting research on juries the current research meets such a requirement as it did not interfere with jury deliberations or court outcomes and was conducted as exploratory research into jury representativeness generally.

3.6 Contribution of the study

Criminological research is not merely undertaken for the benefit of academic disciplinary advancement but also to impact on government policy and to advocate for developments or change in social policies and practices of the criminal justice system (Chamberlain, 2013). It is hoped that the findings from this research will contribute to the generation of policy and procedure surrounding the selection of juries, specifically how they can reflect, to a greater extent, a representative sample from the communities from which they are drawn. This research will generate knowledge on jury representativeness in the Irish context where there is a gap at present by providing specific data on how jury representativeness is impacted at each stage of the jury selection process. As a result, this research has the potential to have wide ranging benefits for society as a whole.

3.7 Limitations of the Study

Firstly it must be acknowledged that while the number of participants in this study may meet the requirements of being a representative sample, it must be acknowledged that there were two jury pools examined. Therefore, the research findings can be said to represent a snapshot of the numerous juries that are sworn in on a national scale annually. Secondly, with regard to the use of the observational method, those who observe may have an unintended influence on the proceedings in question by their very presence (Morgan et al., 2016). The author also needs to be cognisant of their own bias when engaging in observational data gathering methodologies. One’s own experiences and perceptions can influence these viewpoints and so the observer must ensure that they gather all evidence and not simply notice evidence that fits in with the hypothesis of the research questions (Maxfield, 2016). This is especially important as there was no co-observer. It is also important to note that due to the small scale nature of the observation milieu there was the danger of over generalising the position of representativeness on a wider scale (although the statistical analysis will go some way to rectifying this situation).

The reliability of the observational method also needs to be questioned in this respect because the manipulations of variations (or control over extraneous variables) which influence cause and effect relationships cannot be established (McCloud 2015). Consequently, the observational model was not used to determine the causes of certain behaviours and is not meant to be illustrative of the actual representativeness of the selection process. It is a vehicle for contextualising the reality of the selection process and witnessing the practical hands on methodology of such a process as it takes place. So the author’s actions within the observational process were informed by her being cognisant of not over generalising, ensuring an accurate reflection of proceedings by reporting all verbal interactions observed, ensuring that no determinations were made at the point of the data gathering process and being faithful to the transcribing of notes after the observational activity had ceased (Morgan et. al., 2016).

In terms of the statistical analysis of large quantities of information it is important to allow the information to inform the research question as opposed to answer it. Statistics can be one dimensional and easily manipulated and as such the author has taken care to juxtapose the information gathered with her own observational methodology findings (Peck, 2016). This combination needs to report its conclusions without the influences of a proof driven analysis. The research question has optional conclusions and as such this gives licence to the author to stand back and see what unfolds within the context of the study.

Chapter 4 Presentation of Findings

4.1 Introduction

This chapter will present the findings by plotting the stages involved in selecting a jury panel from the point at which summonses are issued to potential jurors through to the final jury being sworn in. The findings will identify what happens at each of the screening processes involved in jury selection. In so doing, it pieces together a comprehensive account of jury selection and forms the platform from which jury representativeness can be examined in the discussion chapter.

As outlined in Chapter 3 there are two stages involved in the selection of juries in court offices in Ireland. The first stage (the administration stage) involves issuing a summons to a randomly selected number of individuals by a computer programme from the Registrar of Electors. The second stage (the court stage) involves the process of jury selection in the courtroom during which a jury is sworn in. The findings from this research are broadly structured around these two stages. The first phase of findings presents demographic data on potential jurors and detailed information on how a large pool of randomly selected individuals (typically 450 to 500 individuals) filters down to form the final jury panel of 12 individuals. This phase draws on comprehensive analysis of court records. The second phase of findings focuses on the data that emerged from the court observations undertaken for the study. Collectively the findings chapter tells the story of the process and the outcome of jury selection based on two cases in a court location in Ireland.

4.2 Main Findings – Quantitative

4.2.1 Gender

The first case study included 450 individuals summoned for jury service, while the second consisted of 480 (both groups are represented separately at Appendix A). As outlined in Table 1 above, these randomly selected groups of potential jurors consisted of a slightly higher proportion of females (55%) than males (48%). The gender breakdown broadly reflects Central Statistics Office (CSO) data which identifies that there is a ratio of 100 females to 97.8 males living in Ireland (CSO, 2016).

4.2.2 Age

Under this heading it is noteworthy that almost one-fifth of individuals (18%) across both case studies did not provide details of their age in responding to the jury summons despite it being requested. Of the remainder, 10% were aged 18 to 30 years, over one-third (35%) were aged 31 to 50 years, 26% were aged 51 to 70 years and 11% were aged over 70 years (Table 1).

Comparative analysis of the age profile of the random sample with the CSO figures for the number of individuals belonging to those age categories and residing in the geographical location under study found that those aged 21 to 30 were under-represented and those aged 18 to 20 years were severely underrepresented. For example, in the four age categories 41-50, 51- 60, 61-70 and over 70 between 0.43% and 0.48% of the population belonging to these age groups were represented in the random sample selected. This compares to 0.27% of those aged 21-30 and 0.06% of individuals between the ages of 18 and 20 (Table 1).

4.2.3 Occupational status

Previous research argues that occupational status is a factor to take into consideration when determining the representative nature of juries (Jeffers, 2008). Occupational status was systematically recorded for each of the 930 individuals across the two cases in this study and categorised based on the occupational categories used by the CSO. A percentage breakdown of potential jurors belonging to each occupational category compared to the numbers randomly selected from those occupational categories was established. Findings revealed that 0.38% of those employed in professional occupations; 0.38% of other employed individuals, 0.44% of retired persons, 0.27% of those unemployed and 0.14% of students were represented in the random sample. In terms of the specific breakdown of the jury summons sample, 17% held professional occupations, 29% were in other employment, 17% were retired, 4% unemployed,5% students, 13% did not state their occupation and 15% did not respond (for full details on all occupational groups represented please see Appendix B). With the exception of culture, media and sports occupations and secretarial and related occupations, all other occupational groups were represented in the random sample of individuals summoned for jury service.

4.2.4 Jurors who accepted the summons to perform jury service

A total of 85% (n=793) of the total number summoned for jury service completed and retuned their jury summons to the court office in both case studies. There was no response from 65 and 72 potential jurors in Group 1 and Group 2 respectively. A noteworthy finding was that of the individuals who completed and returned their summons to the court office (n=793), only 22% in Group 1 and 20% in Group 2 confirmed they were in a position to perform jury service on the proposed date (for a breakdown of figures see Appendix C).

It is argued that these findings are critical in the context of this study in that 78% and 80% respectively of potential jurors summoned were not in a position to attend for jury service. While the information which follows will reveal the reasons given as to why this was the case, one would have to question why over three quarters of those summoned were not in a position to perform their civic duty. Perhaps such a low acceptance rate may provide some explanation as to why court offices summons such a high number of individuals in the first place.

Health professionals represented the lowest acceptance rate for jury duty relative to the number called from that occupational category. Of the 34 health professionals summoned, none accepted the summons for jury service (a breakdown of the number from each occupation summoned relative to the number who accepted is at Appendix B).

4.2.5 Ineligibility and disqualification

Under Section 7 and Section 8 of the Juries Act, 1976, potential jurors are deemed ineligible or disqualified from serving on a jury either due to their occupation, for specific medical reasons or if they have a previous criminal history1 . Findings revealed that 6% of potential jurors in Group 1 and Group 2 respectively claimed ineligibility or disqualification. Across both groups 48% of the total excluded claimed ineligibility due to mental illness. Twenty per

1 Individuals employed in the criminal justice system, incapable persons described as having an insufficient capacity to read, deafness or other permanent infirmity or those with a mental illness which requires hospitalisation or regular treatment by a medical practitioner make up the list of ineligible persons. Those who have served a term of imprisonment of 3 months in the past 10 years are disqualified as are those who have been detained in St. Patrick’s Institution or a corresponding institution in Northern Ireland for 3 months or more are also disqualified.

cent were ineligible due to being employed in the criminal justice system with a further 18% claiming an intellectual disability. Nine percent of individuals reported being ineligible due to a brain injury, a hearing impairment or a physical disability. Five percent were disqualified as they had served a prison sentence of three months or more in the previous ten years.

In compliance with the Juries Act, 1976, all ineligibility claims made due to medical reasons were medically/professionally certified.

4.2.6 Excusal from jury service by the county registrar as of right

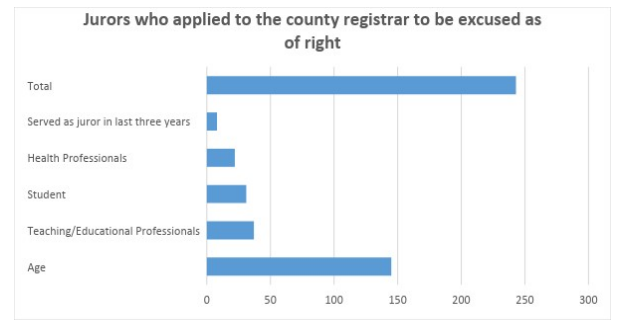

Under Section 9 of the Juries Act, 1976 individuals have the right to be excused from jury duty if they satisfy certain criteria such as the occupation they are employed in or their having served in the recent past as a juror. This list of occupations excused as of right are set out in the Juries Act, 1976 and include many professional groups, medical professionals, individuals employed by the State and those in Holy Orders. In this research, 24% (n=107) individuals claimed excusal as of right from Group 1 summoned and 28% (n=136) from Group 2 summoned. Such excusals represented 26% of the total number summoned for jury duty. Age (60%) emerged as the main reason given for excusals across both groups followed by working as a teaching or educational professional (15%), being a student (13%), working as a health professional (9%) or having served as a juror in the last 3 years (3%). The numbers under each category who claimed excusals for both groups are shown below.

While those who claimed excusal as of right were entitled to do so under the Juries Act, 1976, the impact of such excusals was noteworthy with regard to the impact on the representative nature of the jury pool.

4.2.7 Excusals by the county registrar for good reason shown

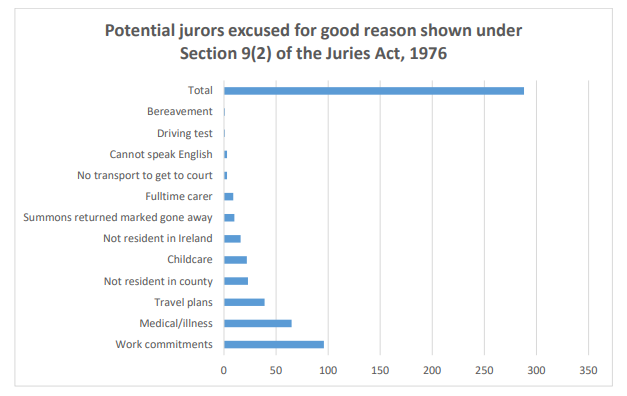

Section 9(2) of the Juries Act, 1976 further permits the county registrar to excuse potential jurors if they show good reason why they cannot perform jury duty on the date requested.

Overall, the data identified that excusals for good reason shown resulted in the removal of almost one-third (31%) of the total number of jurors summoned across both groups. In total, 140 potential jurors (31%) from Group 1 and 148 (31%) from Group 2 sought permission to be excused through this route. The four main reasons under which excusals were claimed for both groups were work commitments (33%), medical reasons (23%), travel plans (13%), not being resident in the county under study (8%) and childcare (8%). Other reasons included not being resident in Ireland (6%), gone away (3%), working as a fulltime carer (3%), no transport to get to court (1%), inability to speak English (1%), and other issues (driving test and bereavement) (1%).

Again it is argued that these findings are critical in the context of this study with regard to the impact they have on the representative nature of the group from which a jury can be selected.

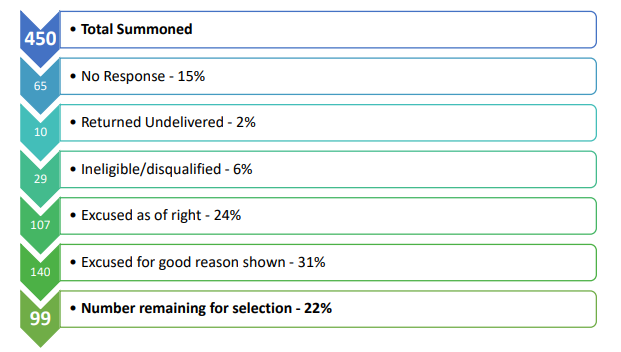

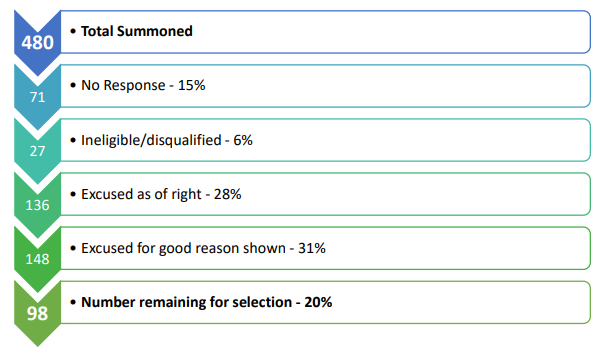

At this stage of the research, quantitative analysis has revealed that in respect of Group 1 there are 99 potential jurors who have confirmed their attendance for jury selection out of a starting total of 450. In respect of Group 2 there are 98 potential jurors who have confirmed their availability to attend from a total number of 480. As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 overleaf, the filtering of the jury pool through the jury selection process has resulted in a considerable reduction in the numbers that will report to court for jury selection.

Consequently, across both groups, just over one fifth of the potential jurors called will comprise the jury pool from which a jury can be selected. Those who no longer form the jury pool from which the final jury can be selected are 15% (n=137) who failed to respond to their summons, 6% (n=56) who satisfied the disqualified or ineligibility criteria, 26% (n=243) who were excused as of right and 31% (n=288) who were excused for good reason shown. With regard to Group 1, 351 potential jurors are no longer available for selection and in respect of Group 2, this number amounts to 382. The visuals which follow represent this information and the starting point from which the observational section of data collection commenced in this research.

4.3 Main Findings – Qualitative

This section tracks the numbers remaining for selection from Groups 1 and 2 respectively and charts the pathway of these potential jurors from their attendance at court to the final jury panel of 12 being sworn in. Before doing so, the context is set by providing a description of the court and court proceedings. On all dates when the author attended court but specifically on the two dates the juries were sworn in, there were a large number of people present. These included the circuit court judge, court staff, potential jurors, Gardaí, prison officers, barristers, solicitors, reporters, probation officers and defendants.

Group 1 comprised 99 potential jurors who accepted their jury summons. In this group 85% (n=84) were employed, 4% unemployed, 3% retired, 1% student and there were no details provided regarding occupation for 7%. Group 2 comprised 98 potential jurors who accepted their jury summons, 76% (n=74) reported being employed, 3(3%) were retired, 1(1%) was unemployed, there were 7 (7%) students. No details regarding occupation was available for 13(13%) of individuals.

4.3.1 Physical description of the courtroom

The same courtroom was used on all four occasions proceedings were observed. A judge’s bench, which was raised by comparison to the general seating area of the remainder of the courtroom was located to the centre of the back wall. Directly behind this bench was a door leading to the judges’ chambers or waiting area and it is through this door that the judge entered the courtroom to signal the start of proceedings. To the left hand side of the bench was a seating area to accommodate 12 individuals and this was where the final jury panel would sit when chosen. To the front of the judge’s bench and again raised and centred to the room was another bench where the court registrar sat to face forward toward the courtroom. To the front of this bench and on ground level were three long tables one placed behind the other and again centred to the floor space of the room where barristers and solicitors sat. All aforementioned benches and tables had microphones on them.

Besides two further designed seating areas marked ‘Press’ and ‘Garda’ containing 6 and 12 seats respectively, the rest of the courtroom was given over to a general seating area where all other people were permitted to sit. There were three doors which facilitated entry to and exit from the courtroom for all other court users.

4.3.2 Call-over by court registrar

Proceedings across all observed events began with the court registrar explaining to potential jurors present what was going to happen. They were advised that they would be called by their name and their corresponding juror number and were asked to respond when called. They were also informed that a jury would be required if the defendants before the court pleaded not guilty. (A detailed breakdown of proceedings observed on all four dates is available at Appendix D).

A call-over to establish who was present was then conducted and as potential jurors acknowledged their presence, their corresponding jury number was placed in a wooden box. For those who did not answer, their numbers were placed to one side. During the callover session for Group 1, 14% (n=14) of potential jurors did not respond. In respect of the Group 2, 10% (n-11) did not respond. On completion of the call-over potential jurors were advised by the court registrar to remain in the courtroom until the judge advised them otherwise.

What was notable were the 14% and 10% of potential jurors who did not respond when called. It was assumed by the author that contact had not been made by these individuals with the court office to say their circumstances had changed since they initially confirmed their availability for jury service. Otherwise, why would their names have been called? Also notable were the 26 (3%) potential jurors across both groups who had attended in court but who advised the registrar that their names had not been called during the call over. In relation to those who showed up when not expected and those who failed to do so when they were expected, it was not possible to identify why this was the case.

4.3.3 Waiting time between call over being completed and the judge coming on to the bench